On tree species – Sur les espèces d’arbres

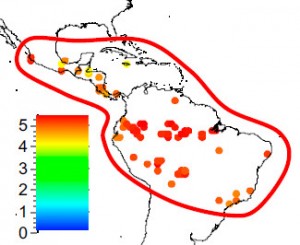

We have the pleasure to announce the publication of another high profile paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America: “An estimate of the number of tropical tree species.” This paper (see the PNAS website after mid-June 2015) results from an international collaboration of ecologists and was put together by our colleague Ferry Slik of the University of Brunei at Darusallam. Why such a paper? Well, we don’t know yet the number of tree species on Earth. This is a shame (governments are mostly not interested), because we are losing species at a huge rate. At the same rate provoked by the meteorite that destroyed the Dinosaurs. Humans are the cause of a major mass extinction. Is it important for our daily life? No, so far, so good: everything is good before an accident.

Nous avons le plaisir d’annoncer la publication d’un article dans la revue prestigieuse Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America: ‘Estimation du nombre d’espèces d’arbres tropicaux’. Cet article (voir le site PNAS à la mi-juin 2015) résulte d’une collaboration internationale entre écologistes et a été écrit par notre collègue Ferry Slik de l’Université de Brunei à Darusallam. Pourquoi un tel article ? Eh bien figurez-vous qu’on connait encore mal le nombre d’espèces d’arbres à l’échelle de la Terre. C’est une honte (les gouvernements ne sont que symboliquement intéressés), car nous perdons des espèces à un taux élevé. Aussi élevé que celui provoqué par la météorite qui a détruit les Dinosaures. L’humanité est responsable d’une extinction de masse. Est-ce important dans notre vie de tous les jours ? Non, il ne faut pas se plaindre : tout va bien avant un accident.

Jean-Philippe Puyravaud