The ultimate tragedy of the commons?

Some of our colleagues and friends who are social scientists think of us conservationists as neocolonialists and/or pro-capitalists when we say that forests should be more protected. They often view forests as an ill-managed resource because for them (i) forest management is inherited from the British colonial rule, (ii) the poor need to have control over their environment and (iii) if local people do not manage their environment, other forces will.

I am originally from working class and I am systematically grieved to find myself clubbed with bad guys proposing to rip-off the poor of their scant resources. It is funny that these views often originate from fairly privileged left-wing people. Not that there is anything wrong to be left-wing and privileged. But whether from working class or more privileged extraction, there is a danger in creating a narrative on the basis of self-righteousness and paucity of data. The examples of locally protected forests that demonstrate sufficient size and ecological viability are by far too rare. We have however access to ample scientific data showing beyond doubt that the biosphere is getting destroyed at a rapid pace. If the forest was really cut for the poor, then it would be a lesser evil.

I never believed that access to forest resources would carry the poor out of poverty. In the early 1990s, it was clear to my colleague Jean-Pierre Garrigues and I, that landless laborers were working for “rich” farmers to extract manure, fodder and non-timber forest products from the forest. A simple way to “help” the poor, would have been to provide regular jobs. But even today, thirty years later, many people have lost their income because of the COVID-19 lock down: there are still daily wage workers.

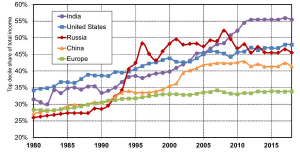

Where do the resources generated by deforestation go? Thomas Picketty, the author of “Capital in the Twenty First Century”, a must-read book, may have an answer. If you look at the figure below (https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/03/pikettys-new-book-explores-how-economic-inequality-is-perpetuated/) you can see that economic inequality has increased since the 1980s (and probably earlier). The figure shows the share of total income by the top 10%. This trend is of enormous magnitude with astounding social consequences.

It would be tempting to correlate the decrease of primary forest cover (for example here) with the increase of inequality. And I have a suspicion: like most economic activities, forest destruction may benefit the poor only marginally. This would be the ultimate tragedy of the commons.

Jean-Philippe Puyravaud